|

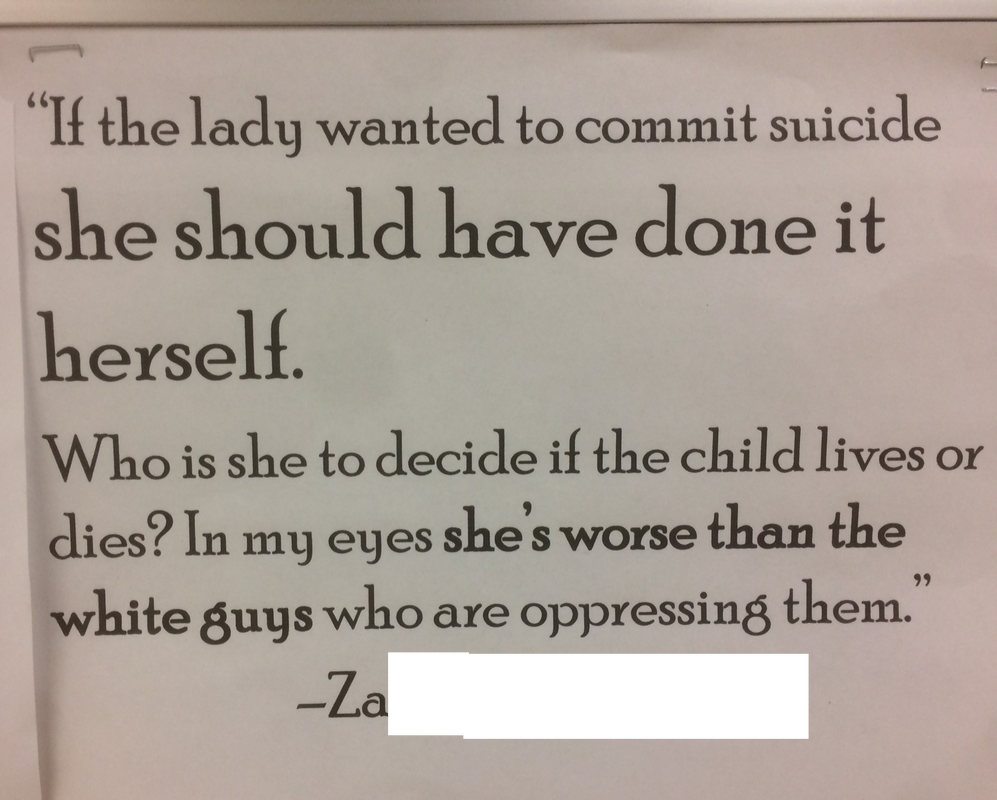

So…how do you expect Muslim students to react when they read “God is dead”? The novel Night by Eli Weisel has been a commonly read novel in American colleges and high schools for at least 2 decades. I remember being assigned to read it in high school in the late 1990s, and now in 2017 as a high school teacher I find students assigned to read it also. In the western world it has been a highly read and praised novel. In the general contexts of American schools that have been typically devoid of Muslim students and Muslim or Islamic perspectives, novels like Night and it’s philosophical themes of suffering and religio-existential development could be analyzed by students entirely within a vacuum of western culture. The United States has been a traditionally Christian nation, but it can be safely stated that anti-religious sentiment and lessening religious practice has been a recurring theme in US society and Western Europe since at least the mid 19th century. Literary works and much lauded authors of American and European background during this time have been prime catalysts for the advancement of this waning religious sentiment. Night (1956) is an example of such literary work. The Crucible by Arthur Miller (1953) is another example; as a are works such as The Plague (1947) by Albert Camus, and the works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky and others in that vein of literature. These books and authors are common parts of high school literary curriculum. The latent (or blatant) presence of existentialist thought in these books is apparent to the eye that is educated in the philosophical and literary trends of the time period; but to what extent is it apparent to our high school students? And to our Muslim students who come from a vastly different cultural and religious background? Existentialism, generally, is wholly antithetical to Islamic values; and the themes of these books often leave Muslim students not knowing how to react, or often with an inner feeling of disgust that they may not have the skills to articulate (so they just remain silent on it). Considerations of these questions means that the trend of influence that existentialist philosophy had on early 20th century literature (and culture) ought to be taught explicitly to students in high school, as this will enable them to recognize recurring trends and themes across different works of literature. It can also help them understand some origins of certain cultural phenomena that still exist in the vacuum of western world but do not take hold in the Muslim world; and the more that books are connected to having an effect on modern times the more engaging they tend to be to all students. If we are to ask the question as to how history has influenced literature or any book the preface and foreword to the book are often used to draw the reader’s attention to the book’s central themes and their historical or societal impact. In the case of the 2006 edition to Night (copyrighted 46 years after it’s first publication in English but newly translated by Weisel’s wife) and in the original forward by François Mauriac both men state rather clearly that central to the importance of Night are the conclusions that the young Jewish Eliezer (the boy who narrates the book) draws about God. It does not take long for the Muslim student to get into this book and be confronted with brazen statements and assertions that are affronting, abhorrent, and wholly antithetical to Islamic values (and of course, it is quite alright for students to be confronted and challenged with things they do not agree with in education, but the question here is how to provide frames of analysis for this material so that Muslim students find value in reading it, and are therefore engaged in the literary work, and not just dismissive). In the foreword Weisel talks about how the early translations from the Yiddish version actually took parts out that showed just how negative the narrator’s view towards God and faith had become by the time he had written the book. He says that the Yiddish version opened with the lines, “In the beginning there was faith—which is childish; trust—which is vain; and illusion—which is dangerous. We believed in God, trusted in man, and lived with the illusion that every one of us has been entrusted with a sacred spark from the Shekhinah's flame; that every one of us carries in his eyes and in his soul a reflection of God's image. That was the source if not the cause of all our ordeals.” Wiesel goes on to talk about how it was initially difficult to get the book published, and how Rabbis were against it. However, it would go on to became widely famous and is now taught in schools across America. From the forward Mauriac writes about what he calls the “extraordinary aspect of this book that has held (his) attention”: “The child who tells us his story here was one of God's chosen. From the time he began to think, he lived only for God, studying the Talmud, eager to be initiated into the Kabbalah, wholly dedicated to the Almighty. Have we ever considered the consequence of a less visible, less striking abomination, yet the worst of all, for those of us who have faith: the death of God in the soul of a child who suddenly faces absolute evil?” So Mauriac finds it to be something extraordinary that a religious child goes through an experience that causes him to experience “the death of God” in his soul. He then tells the reader to consider what is going on inside the child’s mind as he recounts the narration from the book when Eliezer watches smoke come out of the furnace where his mother and sister are dying in which he says: “Never shall I forget those moments that murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to ashes.” After this Mauriac states clearly what he thinks is very appealing about Eliezer and makes a revealing reference in doing so: “It was then that I understood what had first appealed to me about this young Jew...For him, Nietzsche's cry articulated an almost physical reality: God is dead, the God of love, of gentleness and consolation, the God of Abraham” Mauriac further emphasizes the importance of Eliezer’s thoughts that “God is dead” by talking about a scene where Eliezer witnesses a young boy being hanged and quotes from the narration: “when the child witnessed the hanging (yes!) of another child who, he tells us, had the face of a sad angel, he heard someone behind him groan: ‘For God's sake, where is God?’ And from within me, I heard a voice answer: ‘Where He is? This is where— hanging here from this gallows.’” When Mauriac says, “For him, Nietzche’s cry articulated an almost physical reality: God is dead” the reader would be missing out on a significant perspective on how history informed Night by Elie Weisel if they do not know who Mauriac, the author of the Foreword, is referring to when he mention’s “Nietzche’s cry” in his expressing his awe at the young Jewish boy Eliezer realizing that “God is dead.” And of course the same exact phrase - “God is Dead” - was used by Arthur Miller in The Crucible through the voice of John Proctor when he is in the throes of being condemned to execution by religious zealotry. The student who has the philosophical connections and motivations behind Elizer’s use of the phrasing in 10th grade explicitly, is better able to recognize that same connection and motivation when they read The Crucible in 11th grade. I can recall several (non-Muslim) classmates in high school mostly being persuaded that Eliezer had the right and reason to give up on God in the book due to what he was going through. It is much more difficult to imagine Muslims students (or their family members) who have been through war, false imprisonment, or such horrors as witnessing the execution of their parents as children, drawing the same conclusions. So rather than teaching mere empathy for a character whose heart turns against God as a result of witnessing suffering, to Muslim students we ought to elaborate on the history of the reference here and the theme of God’s death in Night and the history of Weisel bringing this book to print, at the urging of François Mauriac, and the connections between Mauriac, Weisel, and the 19th century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. This is of course is in no way to say that we cannot teach and model empathy for the suffering of the Jews in the holocaust (and in our book list we have a book about how Muslims aided and assisted Jews in Nazi-occupied France) but for Muslim students a distinction between the patent suffering on one hand and empathy for Friedriech Nietzsche’s ideological framework on the other needs to be made, allowed for, and supported. If a Muslim student wants to question Elizer’s right to give up on and blaspheme the name of God, they should not in turned be accused of being a Nazi. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) was a German philosopher. He was very anti- religion and is best known for paraphrasing his philosophy with what was quoted above; that “God is dead.” According to the Encyclopedia Britannica he “became one of the most-influential of all modern thinkers” and “his observation that ‘God is dead,’ ...determined the agenda for many of Europe’s most-celebrated intellectuals after his death.” If some of the dots of that agenda are connected for students it helps them better understand recurring themes in 20th century European literature and therefore helps them to analyze these works critically. One of those greatly celebrated intellectuals being referred to was a French philosopher named Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre and Nietzsche are both well known for expounding on the philosophy of “existentialism” and their works and writings are prominently featured in philosophy courses in Universities. Both of them are well known atheists who believed morality is something that man only defines for himself. Sartre is well known for agreeing with another German thinker of the 1800s, Karl Marx, who believed that religion was only an instrument that the powerful and rich used to control people or that religion was the “opium of the masses” as he called it; and he believed there was nothing in existence beyond the material world and that people and intellectuals should only view the world that way (search these matters on Encyclopedia Britannica if you are unfamiliar with them). After World War II Elie Weisel, according to his autobiography from 1995, went ten years without talking about the war and ended up at Sorbonne University, a well known university in France where Jean-Paul Sartre was a lecturer at the time. It was during Weisel’s time at Sorbonne University that he would write the first version of Night in Yiddish (at the urging of Fracois Mauriac). Wiesel writes about going to the lectures of Jean-Paul Sartre with Mauriac in his autobiography: “With Francois’s (Mauriac) help I enrolled in the Faculty of Letters of the Sorbonne. At last I found my vocation. I have happy memories of my student years. I devoured books on philosophy and psychology...Francois, my tutor, guide, and friend, did his best to initiate me into the life of the Latin Quarter, taking me to hear Sartre and Buber, whose lecture on religious existentialism was an event. The hall was packed, the audience enthusiastic. Buber was treated like a prophet. His listeners were elated, conquered in advance, ready to savor every word.” (Page 154) For Muslim students, it is important to note that these men and their philosophies developed in a world where Islam was something that was not on the cultural radar. Whatever intellectual backing they had to hold religious faith together as youth, Islam played no part in it. When they speak, write, and create philosophies about God and religion it is entirely within a mindset that thinks of history in terms of the Western world and how Christianity and Judaism have existed in Europe (and America). Nietzsche’s pronouncement that “God is dead” meant that “belief in God in the 19th century was no longer tenable” - a question that should be asked and researched around these books are what was the historical context of the 19th century that allowed this atheist philosophy to take place and thrive in latter years? Other critical thinking questions. If Nietzsche made this pronouncement in the 19th century, and Weisel uses the same wording in his book almost 100 years later (and three years after Arthur Miller did the same) what implications does this have for Night as a memoir? Is it possible that Weisel’s education at Sorbonne under Sarte motivated him to include advocacy for Sarte/Nietzsche’s philosophy in the book? Is it fair to ask whether Weisel’s rejection and enmity toward God actually developed at Aushwitz, or could his education later in life have influenced how he portrayed the psychological development of Elizer in the book? An appropriate approach to teaching this book ought to give Muslim students some opportunity to display moral indignation at the character or Eliezer, who loses faith in God and grows to despise his own father for his weakness. Again, turmoil, tragedy, and suffering are commonly known to the Muslim world in the modern era and many of our students come from refugee families with harrowing histories of personal strife where they have come out still (if not more) faithful on the other side through inner strength and striving. The Muslim students should be supported in contrasting this type of view to the cynical portrayals of humanity that appear in Night. The teacher of Muslim students themselves ought to develop question prompts and writing/discussion activities around these ideas themselves as what is standardly available for teaching resources around this book do not elucidate and support this type of critique and analysis. Rather, they generally prompt the students towards empathy with Nietzschean world outlook. The McGraw-Hill Study Guide for the book, for example, asks presumptive questions such as: How do the Jews react to Madame Schäcter’s behavior? What does this reveal about human nature? Madame Schäcter is a Jewish woman who loses her mind on their train to Auschwitz and continually screams about a hallucinatory fire until some of the Jewish boys bound, gag, and whip her; elucidating cheers from the crowd. The McGraw-Hill question here carries the assumption that human nature inclined toward this type of brutality. Study guides and lessons revolving around this book are replete with prompts for students to reflect on the poor treatment of the Jews (which surely all can agree on) and to thereon also reflect on “human nature” - or humans as sinister creatures - and to share in the overall depression and cynicism that is felt by the suffering of young Elizer, which ultimately prompts for an empathy towards Elizer’s character development in the book; i.e. one of a traditionally raised and faithful Jewish boy to one of a cynic who fines strength in “accusing” God. This is a statement and sentiment expressed after Elizer witnesses the hanging of a child - to Muslim students, no matter the gravity of the context, such a statement about God is abhorrent and shocking, and culturally-relevant teaching to them is going to provide a space for them to express moral indignation about such an attitude as well as afford them the appropriate cultural-historical background knowledge in order to critique and question the author’s motivations. An example of the type of indignation that I am talking about and a Muslim student can feel is shown below. This is from a 10th grade Muslim student, an assignment done for a World History class. The students had been learning about the African Slave Trade, they read a graphic novel that portrayed the brutality of white slave captors and the reactions of African tribesmen and women of killing themselves and killing their own infants as a form of resistance to being taken as slaves. Clearly the work is meant to highlight the brutality of the captors and show the extreme ends under suffering that the would-be-captives were pushed to. But generally, Muslim students have little empathy for victimhood; despair, self-pity, rejections of life, and depression are very un-Islamic values. One Muslim student (who herself is a black African) showed this with the conclusion pictured below, a quote from her reaction paper that her teacher hung in the hallway: An interesting activity might be to compare the attitude, disposition, and fortitude of Elizer to the girl in this video in present day Northern Syria. Has not this child “faced absolute evil” as Elizer did in Night? Yet what conclusions can students draw about their contrasting sentiments in the face of such adversity.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

February 2024

\Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed